It was mid-February 2009, when nine months into my first pregnancy I woke up one morning and realised that, for the first time in several nights, I hadn’t been woken up by the usual jabbering of limbs in my abdomen. I went for an orange juice, something that always seemed to get the baby moving… nothing. I walked around a bit, caressed my bump… still nothing. Finally I called the hospital in Kingston, London, where we lived at the time and arranged to go in for a scan.

There is a practical process that follows the death of a child in utero in the latter stages of pregnancy. You are induced (though not always, some doctors prefer to let labour happen naturally), you give birth, you make funeral arrangements, you and your child undergo tests, you go home.

This is the cold, hard, numb reality of what happens. It’s difficult for me to write, but it is what it is. I can’t soften the starkness of it.

While miscarriage and cot death are issues which are dealt with relatively openly in the run-up to birth, and after you take your baby home, stillbirth is an issue which continues to be dealt with in hushed tones. People may know someone, who knows someone who it happened to. That someone is me.

Categorised bluntly, stillbirth is the term given to babies who die in the womb after the 24th week of pregnancy, (although the exact distinction between a miscarriage and a stillbirth can vary from country to country). In Belgium, as in the UK, this 24 weeks or 180 days, is also the cut-off point which entitles parents to maternity leave entitlements as if their child had been born under normal circumstances. For us, our daughter died in the 37th week of pregnancy and I gave birth to her naturally after an induced labour. My husband and I are not alone however; according to SANDS, the stillbirth and neonatal death charity in the UK, on average, 11 babies are stillborn every day in the UK, working out roughly at 4/5 per 1000 births. In Belgium, WHO data on stillbirth from 2009 shows a slightly lower rate of 3 per 1000 births, a figure broadly represented across Western Europe. However, while these statistics are not intended to spread anxiety, there is a need to be aware that stillbirth is a far more common phenomenon than people realise, and there is a need to be able to talk about it openly.

Unlike cot death, which received a huge investment in research in the ‘70s and ‘80s, leading to its dramatic decline, there is surprisingly little research into the subject of stillbirth. It is maybe for this reason that, in the large majority of cases, no real reason is found as to why a baby dies unexpectedly in the third trimester. More often than not, the death of the child is simply classified as ‘unexplained’, a pitifully anti-climatic justification for such a devastating turn of events.

If you or someone you know has been affected by stillbirth, it is important to know that help is available. I found it an extremely isolating experience, but loneliness need not go hand in hand with grief. There are people who share the experience, there are forums where stillbirth can be talked about openly, and there are organisations willing to help. In Brussels, the women’s clinic at Cavell Hospital offers private counselling and a support group for families who have had to cope with the death of a baby at birth or in the first few weeks of life. Online, the SANDS charity (based in the UK) provides support and advice in English, as well as discussion forums for parents to discuss their own experiences with each other, and there is a selected body of literature available on stillbirth and more generally, on coping with the loss of a child. Finally, here in Brussels, the BCT’s own Experiences Register can connect parents who lose a child at birth or shortly before birth.

In my own experience it was hard to seek help. Physically meeting other parents who had gone through a similar experience to us was a major turning point in our path back to normality. It was a relief to be able to talk about the child we lost on ‘equal ground’ without feeling the eyes of genuine pity burning into us. I remember one book I read where the author told how she often wished she had a stack of cards in her pocket that explained what had happened so that whenever the question came up she could just reach in and hand one over. My first child was stillborn, it would announce, saving her the heartache of having to say it aloud herself. I felt exactly the same.

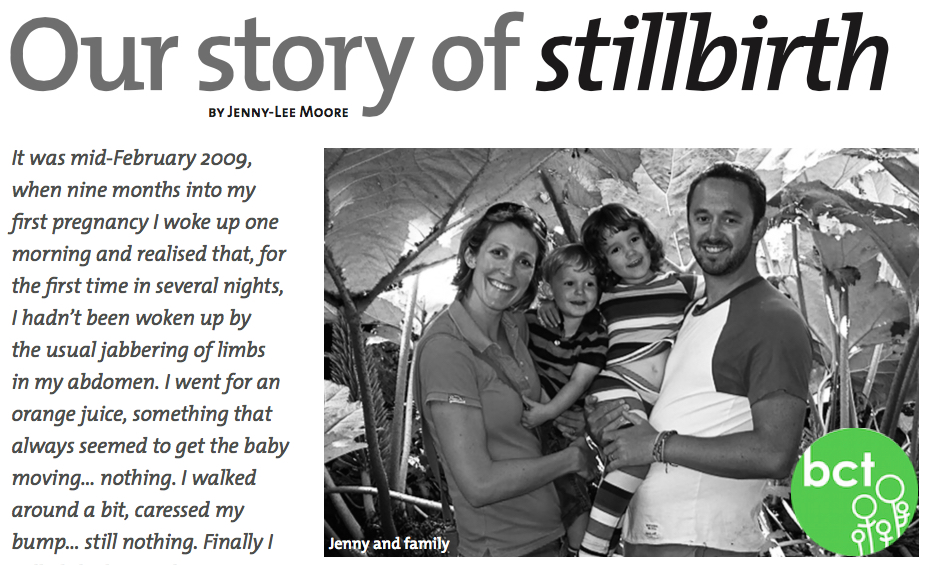

On reflection I learned many things through the death of our daughter. She taught me about the strength of relationships, about the unpredictability of life and about the awkwardness of death. Still now, four years on with two beautiful, healthy children, the simplest conversation can turn into a hopscotch of awkward moments as I try to keep the conversation light. This is why, when I am asked how many children I have, I consider my response with care. Do I simply reply that I have two, or do I include the child that passed away keeping her firmly present in my family’s reality?

I have to decide whether it is harder not to mention her, or whether to have to cope with the mutual discomfort of my own inconvenient truth, and the subsequent apology offered up for disclosing our private little tragedy to a complete stranger: “I’m sorry, I didn’t want to upset you”, (but I felt had no choice).

Most of all however, I learned about survival. We have lived through an incredibly sad experience and have come to the conclusion that in fact we are unbelievably lucky. While I couldn’t believe it possible at the time, we went on to have two more fabulous children. One day Heidi and Barney will learn about their older sister and we will show them her name, engraved on the inside of our wedding rings, and explain how much joy she brought to us in those brief nine months.

The truth is, for any of us who have had a stillborn baby, more often than not we want our child to be remembered. Our first daughter is not a secret. She was one of life’s miracles, deeply, publicly loved. Her death is the awkward, unexpected swerve in the road of our life’s journey, but she is not. She was perfectly formed, serene, beautiful and the most bittersweet epitome of disappointment and pride all rolled into one. Do not be afraid to ask me about her, she continues to live in us every moment of every day. Her name is Elodie.

If stillbirth affects someone you know, try not to leave them to deal with their situation on their own. Do not shy away because you don’t know what to say, simply let them know that you are there for them, for the long term. If stillbirth affects you, help is at hand. You are not alone.

For more information or support:

– in Brussels:

Edith Cavell Women’s Clinic – Paroles de Deuil

Community Help Service – www.chsbelgium.org

BCT Experiences Register (experiences@bctbelgium.org): BCT miscarriage supporter Tina Kenrick is available via this network, and, as a trained EDS volunteer, Jenny herself is also happy to talk to other parents

– online

SANDS UK Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity – www.sands.org.uk

Suggested Reading:

An exact Replica of a Figment of my Imagination by Elizabeth McCracken (2009) pub. Little Brown & Company ISBN-10 0316027669

When A Baby Dies: The Experience of Late Miscarriage, Stillbirth and Neonatal Death by Alix Henley (2001) pub. Routledge ISBN-13: 978-0415252768

By Jenny-Lee Moore

This article was first published in the November/December 2013 edition of the BCT’s Small Talk magazine.